Forget everything you thought you knew about Swiss cheese and journey with me to an altitude of 6,500 feet, where cheese is made over an open wood fire with tools delivered via helicopter.

When I was 15, I flipped through the catalogue of a now-defunct kitchen supply store when an unfamiliar appliance caught my eye. Even the name was foreign: raclette. I stole away to my computer, devouring all I could about this fantastic looking device—a grill, outfitted with removable pans underneath to melt cheese. Although I was already a cheese aficionado by then, I had never heard of such a thing—and I was smitten. I went to the store that very day. Two decades later, I have many fond memories of introducing loved ones to the charming Swiss tradition.

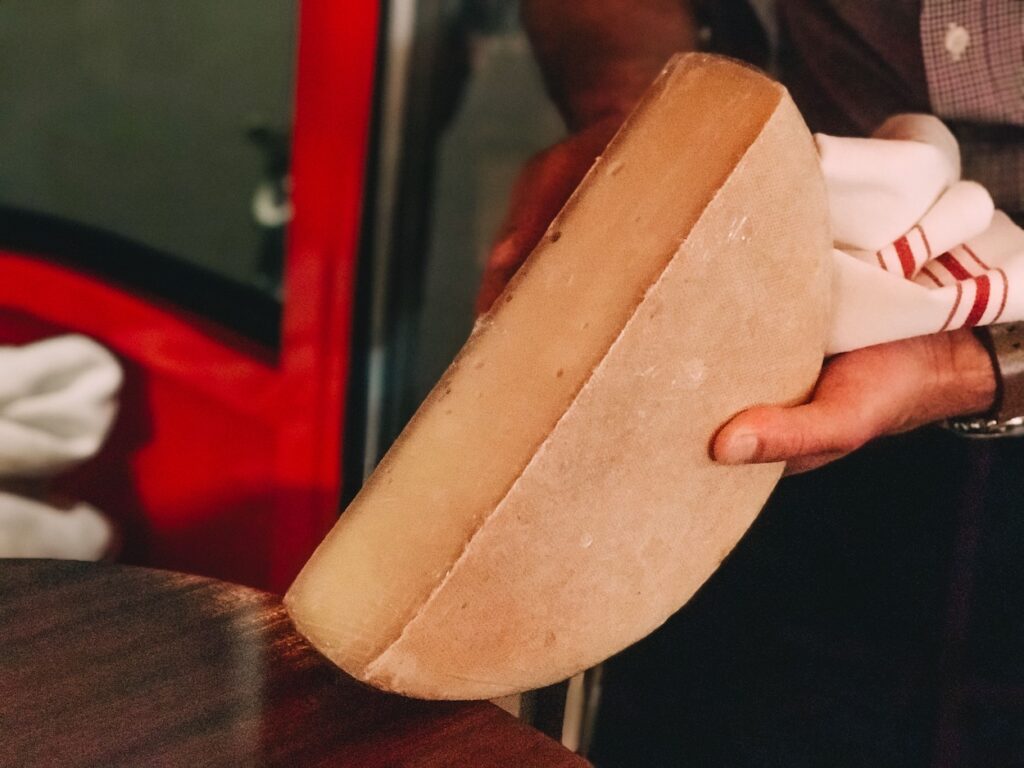

Last year, I enjoyed raclette with my partner for Christmas, scraping golden, aromatic strands of cheesy goodness onto my plate alongside a veritable spread of cornichons, potatoes, and cured meats. Part Swiss, it was he who turned me onto L’Etivaz—the second time I’ve been surprised to be unfamiliar with something cheese-related. A rare Swiss AOP cheese, L’Etivaz is produced in a specific way in a specific region—similar to the AOC designation for Champagne or DOC for Parmigiano Reggiano.

I was told there was no way to purchase the cheese on our side of the pond, which is a surefire way to pique my curiosity and motivate me to track something down at any cost. Researching L’Etivaz one evening, I dove deep into its origins as an Alpage cheese—also known as Alpkäse—and a concept called transhumance at the heart of every Alpage cheese operation. A centuries-old tradition, transhumance is the migration of people and animals in accordance with the seasons. The results of this lifestyle on cheesemaking are simply divine, and these discoveries led me to Adopt-an-Alp, an extraordinary program founded by Swiss expat Caroline Hostettler.

The Munster Incident

It must be said that the term “Swiss cheese” is a bit of a misnomer, doing a disservice to the tremendous quality and varieties of cheese made in Switzerland by reducing it to the single image of a bastardized Emmentaler AOP—the pale, floppy, pre-packaged slices most people recall upon hearing the term. It was a thought similar to this that led Hostettler to found her company Quality Cheese Inc., which imports high-end cheeses from Switzerland. Shortly after moving to the US, she was standing in line at a deli counter when a woman in front asked for Munster cheese “sliced real thin.” Accustomed to the Munster back home in Europe, which is soft with a washed rind, Hostettler wondered how this was possible. She spied the cheesemonger reaching for a large, semi-firm, rindless block—in other words, inauthentic and uninspired. “I thought, okay, I need better cheese in my life than this,” she laughs, recounting the memory by phone. It was then and there that she resolved to bring real Swiss cheese to the US. Packing a cooler with 10 pounds of Sbrinz, Gruyère, and Emmentaler, Hostettler jetted off to five different cities to meet with some of the top chefs in the U.S. When she returned home two weeks later, orders were already awaiting on her fax machine.

As Hostettler grew closer with the farmers behind seasonally-produced Alpage cheeses, she developed a deep respect for their sacrifices which made this particular delicacy possible—namely, the burden of moving up the mountains with their families and herds in order to keep the tradition of transhumance alive. In 2013, Hostettler founded Adopt-an-Alp as a way to unite Alp farmers in Switzerland with American cheese lovers, not only so they could taste the smallest-batch, traditionally produced, authentic Swiss cheeses, but also to understand and appreciate the lifestyle behind the production of Alpage cheeses.

Adopt-an-Alp began with six Alps and 14 US partners. Last year, the program connected 32 Alps with more than 100 restaurants and retailers. Committed to buying a certain number of wheels per year, partners can select an Alp based on factors such as whether they make cheese with cow’s milk or goat’s milk, have a female cheesemaker, or even boast the “most loved” animals. Then Hostettler shares the everyday life of the farmers in an effort to help American cheesemongers understand the practice of transhumance. “I try to constantly communicate the situations they face that we are so [far removed] from,” she says.

Last summer, Hostettler called a farmer to check in, and was told that the family’s oldest cow had rolled off a cliff in her sleep the previous evening. They had to put her down. “It was like they had lost one of their children—it was really, really hard,” Hostettler recalls. She also encourages the farmers to show glimpses into their lives through photographs—whether it’s a still life of the dinner table, milking cows, or grandchildren picking wildflowers—which she posts on Adopt-an-Alp’s blog. “It’s sharing the moments, especially the visual ones, that is so strong. It really helps people understand the different world these people live in. Some [of the farmers] are very shy—they’re not used to being in the limelight. But it’s satisfying because they see now that we want to do something to make them understood; to give them a voice.”

The farmers are also interested in what happens with their cheese, asking Hostettler what the chefs and shops do with the wheels they receive. “With [mutual] understanding, respect and value for each other can grow.” This, says Hostettler, is the most rewarding part of her work.

Higher Standards

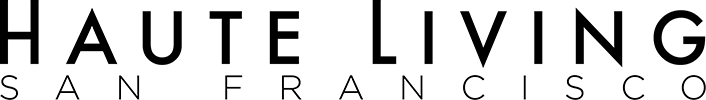

Another record to set straight: “alpine style” cheeses are not equivalent to Alpage. The latter can be made only during summer, high up on a mountain where the environment is extraordinarily pure. “There are no influences such as pesticides or cars,” says Hostettler. “Plus, only a very fit cow can go up, because the metabolism changes with the higher altitude.”

Alpage cheeses must also be 100% farmstead with no exceptions, whereas milk for “alpine style” cheeses is often a mixture of milk from different dairies brought in on a truck. “You cannot transport milk for Alpage cheese, so it’s very organic and wholesome. You know exactly which animals gave the milk. There is complete transparency,” says Hostettler. The program is timely—right now, we care more than ever about the quality of ingredients and their origins, as seen in the nose-to-tail and farm-to-table movements. Alpage cheese, it seems, is the next Wagyu beef.

Another unique characteristic is that the taste of the milk itself changes each season due to factors such as rainfall and how long the snow remains on the meadows, along with the incredible biodiversity of an alpine meadow. Animals graze on 150 different grasses, flowers, and herbs compared to pastures further down, where it’s two handfuls at best, says Hostettler. “All of these little influences are so powerful, and it’s reflected in the cheese.” She hopes that people will realize the value of Alpage cheese once they understand these special circumstances under which it is crafted. She even recalls one Alp that is only able to receive provisions such as fresh clothing and tools by helicopter. “This is made at an altitude where you have to hike up; everything’s more complicated and cumbersome. People need to know that in order to be able to really appreciate those cheeses.”

The admiration is apparent in Hostettler’s voice as we discuss L’Etivaz, the Alpage cheese that led me to Adopt-an-Alp. Made in the eponymous village amid the Gruyère-producing region, she tells me that Gruyère producers tried to persuade L’Etivaz makers to give in and join them for decades, to no avail. L’Etivaz producers have continued to operate independently to this day, renouncing government subsidies by holding fast in their decision to do so. It’s a courageous stance to take when farmers over the years have given in to selling their milk to large corporations, which guarantees stable revenue in addition to avoiding the treacherous task of hiking and living in the mountains each summer. The L’Etivaz makers’ pride in their product and process strengthens Hostettler’s resolve to spread awareness of transhumance and to garner more support for the farmers carrying on the 8,000-year-old tradition.

Closing the Gap

Five years ago, Adopt-an-Alp began holding a contest for buyers to visit their adopted Alps in Switzerland—meeting the farmers, observing the cheesemaking, and touring their farms in the process. Despite the massive expenditure, Hostettler believes in the life-affirming power of these visits. “We had [one] big, tough guy coming from butchery originally. The whole week, he was so touched. When we parted that last morning, the first one who had tears in his eyes—and then all over his cheeks—was him. He said to us, ‘This has changed my life. I hope, and I believe, that I’m going home as a better man, as a better husband, as a better father.” Upon his return, Hostettler received a photo of home-cooked Älplermagronen—a traditional Swiss dish they had dined on during the trip—that he had shared with his family. “We’re still in touch with him year-round. That’s the thing that makes you think, ‘Okay, it was worth every single thing. Sometimes you work late at night on those blogs, and updates, and lists … and then you see it’s worth it, because this person will, for the rest of his life, appreciate what these people do, and try to share it with his family, his children, and his customers.”

Cheese buyer Omri Avraham of The Cheese Board Collective in Berkeley was one of the lucky winners of the contest in 2017. He recalls: “We drove two hours southeast of Zurich, armed with a set of directions that read: ‘Just keep going up.’” Upon his arrival at Alp Heuboden, he met Fritz, a producer of Glarner Alpkӓse—the newest AOP of Switzerland. During the summer, Fritz, his apprentice Sarah, 65 cows, 20 pigs, and 25 calves live at an altitude of 6,500 feet. Fritz’s wife Anna is responsible for brushing, washing, and flipping the cheese daily in order to ensure proper bacterial development. Avraham watched in awe as Fritz expertly crafted the cheese in a copper vat over a wood-burning fire. “The work is very physical and demanding, but [he] made it look luxurious and magical,” he says. Fritz has been making Glarner Alpkӓse for 13 years—before him, it was his father, and before that, his grandfather. Avraham has such fond memories of the trip he purchased more wheels of Glarner Alpkäse this year.

Meanwhile, Matterhorn Restaurant & Bakery in San Francisco is after my own heart, serving raclette cheese from Alp Maran, as well as fondue moitié-moitié with Vacherin Fribourgeois from Steiners Hohberg—both sourced through Adopt-an-Alp. Natalie Horwath, who owns the restaurant with her husband, Jason, became enamored with fondue and raclette after living in Geneva, and reopened the long-standing restaurant in 2019 after taking over the lease from its previous owners. During the pandemic, they began offering take-home kits complete with burners and equipment. Their bakery offers a delicious assortment of pastries, including a smoked ham and cheese bun made with L’Etivaz, which Hostettler likens to Gruyère but attributes its singularity to the requirement that it be made over an open wood fire. (Once in a while, you’ll even spy a telltale speck of ash in the sea of yellow-ivory.) “It’s one of those cheeses that many people don’t even know the name of, but once they try it, they’re smitten.”

At Its Heart

When Hostettler first started the program, potential buyers could not understand committing to a product they had not only never tasted, but would also have to wait an entire summer to receive. The second year, she had an epiphany: “The program is not just about selling something—it’s advertising a lifestyle and a philosophy. Then, at the very end, comes a product.” It turns out that Adopt-an-Alp is not so much a program about cheese as it is about people. It is about nurturing the connection with our food producers and expanding our awareness of different lifestyles, then deepening our appreciation for both. Thanks to the dedicated efforts of Hostettler, we have the opportunity to savor these remarkable products—the culmination of generations making valiant choices to preserve tradition by prioritizing integrity over income, and heart over haste.