Five living legends of San Francisco describe the forces that propel their passions.

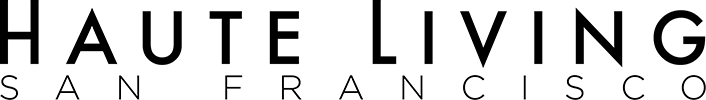

Denise Hale: Caviar with a Side of Civility

Nobody goes to a dinner party because they’re hungry, and those who do probably haven’t been a guest at Denise Hale’s table. The San Francisco hostess, who landed on Russian Hill by way of Europe, New York, and Beverly Hills, is renowned in elite, international circles for “giving wonderful parties,” says a local society maven, “where everyone who anyone wanted to know was there.”

Dinner parties are about socializing—sharing ideas and witty rapport—not devouring food or business networking. Having a collection of famous, jet-setting friends from your world travels to invite (actor Michael Caine and his wife, Shakira; conductor Zubin Mehta; the late fashion designer, Gianfranco Ferre) will help. Even if you don’t, take this advice from Hale: “You always have to invite people with good manners.” This means people who speak to the person on their left as much as on their right, leave their smartphones in their pockets during dinner, and moderate their drinking to avoid becoming too boisterous.

The thrice-married Hale came to New York and Palm Beach from Rome in the late 1950s for the social season after divorcing her first husband. From American gossip columnist Elsa Maxwell, she learned that one-third of a dinner party’s guests should be single, attractive, and interesting. The biggest mistake Hale ever made was inviting to dinner four powerful couples who’d known each other a long time. “They basically had nothing to say to each other,” she recalls. “I was bored at my own dinner party. Hello!”

In Beverly Hills with her second husband, director Vincente Minnelli, she hosted the Hollywood elite in a photo-free zone so VIPs could relax in private. With third husband Prentis Cobb Hale in San Francisco (“the love of my life,” she says; he’s now deceased), she entertained arts, civic, and business leaders, with attention paid to visiting authors and celebrities (Princess Michael of Kent, Dame Edna, David Downton). Strategically seated newspaper columnists spread the word to their readers after dessert.

There’s a currency in connecting people in such a way, as well as lightness and optimism for Hale, raised by conservative grandparents in the former Yugoslavia during the Nazi and Communist occupation. “I’m curious to meet any kind of new people,” she says. “Dinner parties are important for seeing old friends, being with friends, and meeting new friends—past, present, and future.”

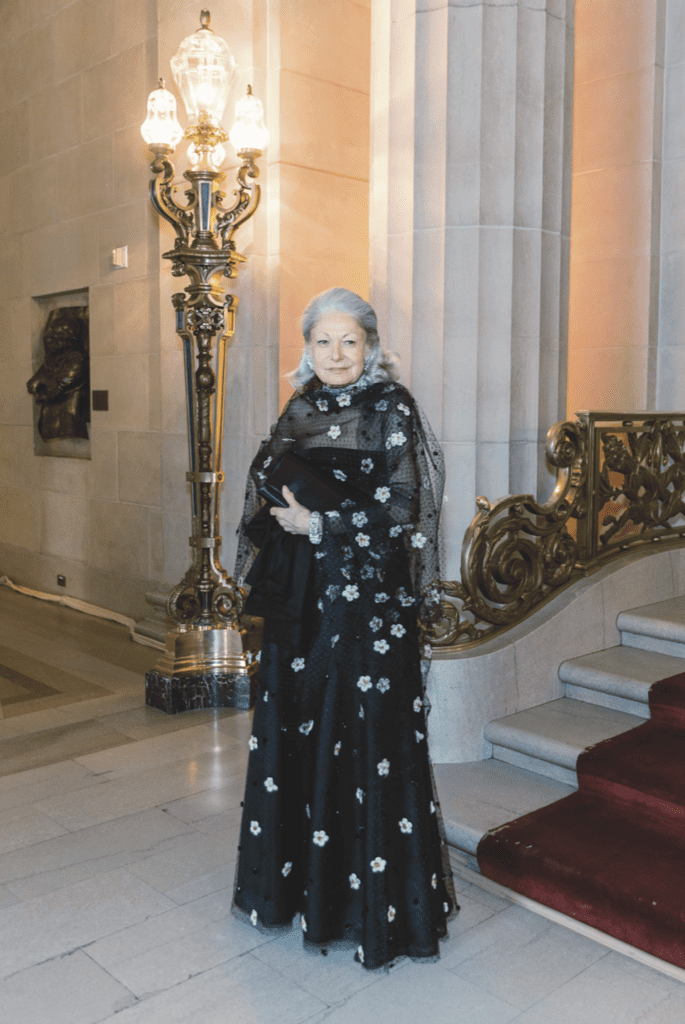

Lois Lehrman: The Right Place at the Write Time

Lois Lehrman never had a problem walking into a room, but her self-assurance at galas and dinner parties didn’t spring from her title as publisher of the Nob Hill Gazette. It came from experience. In the 1970s, she was the only woman to sell insurance at the male-dominated firm of J.I. Kislak in New Jersey. Nervous before her first big pitch, she asked a colleague for advice. “Just turn the doorknob to the right and walk in,” he advised. She did and sold the client a million-dollar policy. “You’ve got to open the damn door,” says Lehrman, who celebrates a milestone birthday in August. “Get beyond that, and you can go further.”

Opening doors became her legacy, literally and figuratively. She met people whose causes she championed in stories that raised awareness among the Gazette’s wealthy and influential readers. Photographer Ray “Scotty” Morris deemed the magazine the “Holy Bible of San Francisco society.” Lehrman, who joined as advertising director in 1981, spread the gospel from 1986, when she bought the magazine from founder Gardner Mein, to 2016, when she sold it to businessman Clint Reilly.

She enjoyed running the annual eligibles and best-dressed lists, along with breezy fare like “How Gala Girls Get Their Glow.” She honed story angles with her upscale audience in mind, like the environmental piece on oceans that focused on why pollution made it impossible for oysters to create (pricey) golden South Sea pearls. “Everybody read that, but if I’d said, ‘The ocean will die if you don’t preserve it,’ nobody would have,” she says.

Under her tenure, the magazine’s motto—“An attitude, not an address”—prompted critics to dub it the “Snob Hill Gazette,” which Lehrman, no elitist, brushed off. She once famously put a picture of a baboon hugging a newborn on the magazine cover to signify Mother’s Day. “I tried to approach everything with a bit of humor, attention to who was reading it, and no preaching,” she says.

In recent years, she has focused on her health (lung cancer, now in remission), and noticed dramatic shifts in the scene, from old money families to VIPs with tech fortunes. “I covered an era of high society that meant something different then than what it means today,” she says. “There were a lot of good people doing good work. I hope the magazine helped foster that and made people feel good about donating and making the city an exciting place to live.”

Shauna Marshall: Rebel With a Cause

When people say Shauna Marshall has changed history, it’s no exaggeration. She was a civil and criminal prosecutor for the U.S. Department of Justice antitrust division. She helped desegregate the San Francisco Fire Department and bring women into the firehouse through a class action suit by Equal Rights Advocates, where she worked in the 1980s. In the 1990s, as the director of the East Palo Alto Community Law Project, she focused on education equity, economic development, and affordable and livable housing. The group blocked a major redevelopment plan, which was ultimately retooled to provide more benefits to residents of the low-income city than developers had initially proposed. Marshall also taught at UC Hastings College of the Law, rising to academic dean. She worked to enhance clinical and pro bono programs, retiring in 2014. In 2020, she helped create the school’s Center for Racial and Economic Justice and still teaches a course on race, racism, and American law.

What else could one expect from a woman who’d been a rebel since childhood? The daughter of a social worker and a lawyer in Great Neck, New York, Marshall was influenced by her grandparents. On the maternal side, they were West Indies immigrants, social justice activists, and union leaders. Her paternal grandfather, meanwhile, was a key figure in the Marcus Garvey Black nationalist movement after World War I. “At the dinner table, we talked about issues of social justice and economic inequality and racial inequality,” Marshall recalls.

In grade school, she staged a protest over a policy that allowed only boys to use basketball courts at recess. In high school, she convinced her father to talk to the president of a local temple in a bid for meeting space—Marshall and her classmates were planning a walkout to protest the Vietnam War and needed a place for a teach-in. “I always had my ideas of how to change the world,” she says.

More recently, Marshall has been active with the nonprofit Presidio Dance Theatre, motivated in part by family history. Marshall’s mother sought to be a ballerina, but the racism of the era prevented her from taking the stage. This nonprofit’s mission resonates with her because it’s centered on uniting diverse communities through the arts. “People are always surprised I’m on the board of a dance theater, but it brings me joy. I love that it uses the arts to bridge cultures,” Marshall says. “It’s perfect.”

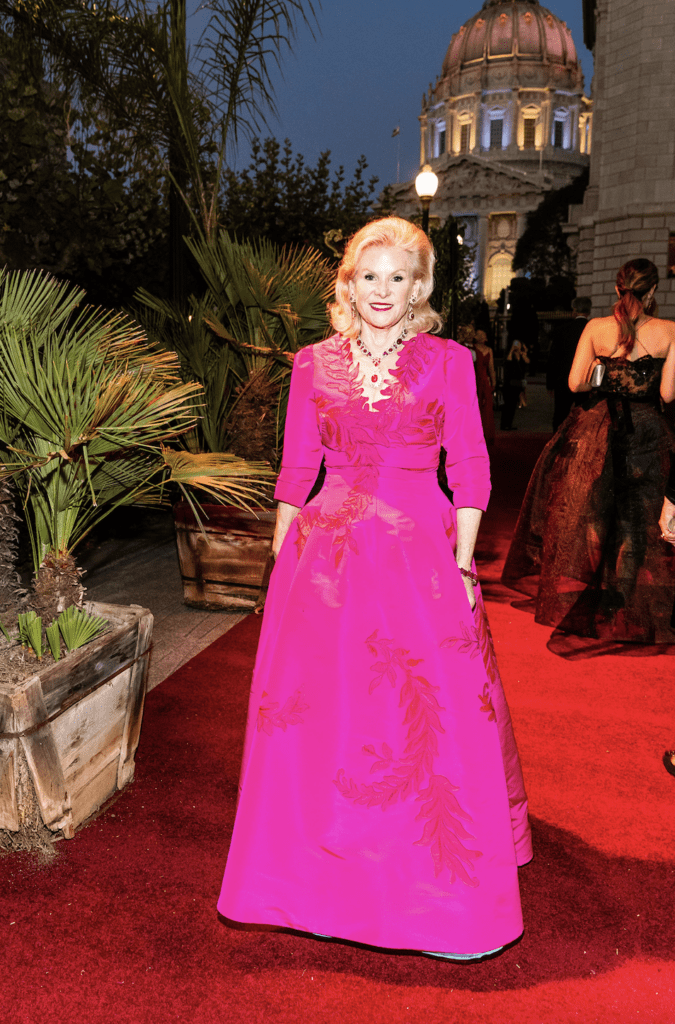

Cissie Swig: Ladylike, With Large Impact

Charisma. Volume. Force. For some leaders, these are the keys to success. As one of San Francisco’s most respected philanthropists, Roselyne “Cissie” Swig finds another quality to be highly effective: listening. “When people feel comfortable and that they’re being respected for what they say, you have a much better opportunity to establish a relationship and move forward together,” she said. “Actions speak louder than words.”

During the past five decades, Swig has helped to shape the arts, create programs for victims of domestic violence, and support Jewish heritage and culture, among other things. She founded two businesses, ComCon International, a consultancy on building community, and Roselyne C. Swig Artsource, an art advisory firm that brought artists and collectors together. She joined the so-called “women’s board” at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1966, and her efforts continue today, with seats on 18 boards, from KQED to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art to the Jewish Community Federation, to name a few. She was appointed director of the U.S. Department of State Art in Embassies under President Bill Clinton; is a Rockefeller Foundation policy fellow; and is a Harvard Advanced Leadership Fellow, too.

All this—in addition to being a mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother—would be dizzying for some. Not for the Chicago native who hailed from a large family, went door-to-door collecting for the March of Dimes in grade school, and says helping others is part of her DNA. “My parents always stepped forward when things had to be taken care of,” Swig recalls. “There was a lot of respect for that.” (While attending UC Berkeley she met future husband Richard Swig; he died in 1997.)

In turn, she shows respect for others. After a spate of negative media about Bayview-Hunters Point in 2010, she and John Boland, the former CEO of KQED, went there to find out what merited such coverage. From that curiosity and neighborhood interest, the Bayview Alliance was formed. For 11 years running, representatives of social service agencies (27 at latest count) have gathered monthly to collaborate on progress and concerns.

Swig can’t list her proudest accomplishment, noting, “It’s a group effort, always.” What she’s found surprising in her charitable work is how many different reasons people have for giving, how many people who could give don’t, and how much potential there is to do more. “There is so much joy in giving back,” she says.

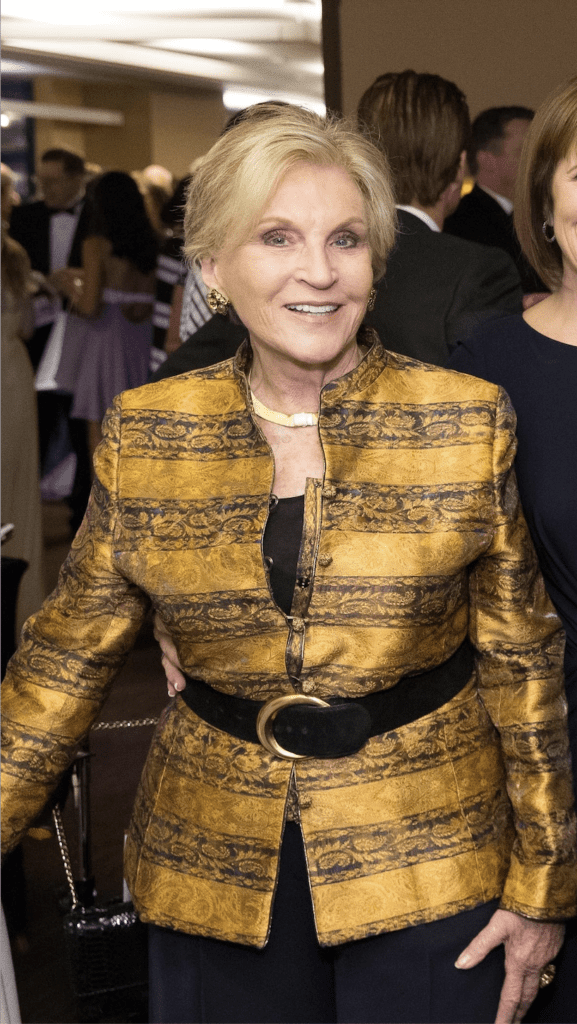

Dede Wilsey: In the Spotlight for Deserving Causes

As a girl, Diane B. “Dede” Wilsey dreamed of becoming a musical comedy star like Debbie Reynolds. Later, she shifted her sights to business school; however, back then, options were limited, even for the daughter of diplomat Wiley T. Buchanan, Jr. “You could work for Vogue, Town & Country, Bazaar, or a congressman or senator,” she recalls. “That was respectable.” As an adult, her brains and bravura have taken her to center stage after all—some of the largest philanthropic campaigns in San Francisco’s history.

In the past five decades while sitting on a variety of nonprofit boards (and serving as head of the Fine Arts Museums board from 1996 to 2019), she has raised more than half a billion dollars for institutions, including Grace Cathedral, the deYoung Museum, and UCSF Medical Center in Mission Bay. Her success stems from her frankness about wealth and the civic responsibilities that come with it and knowing which arms to twist, thanks to relationships developed on the social scene as the wife of shipping executive John Traina, and after a divorce, businessman Al Wilsey (both now deceased).

Wilsey’s passion for change is explained, she says, by her love of ironing. “You look at something with wrinkles and you make it smooth,” she notes. “I like fixing things.” Wilsey made her first charitable donation in grade school—$2.50, half her monthly allowance—to a Christmas project that raised $27 for turkey dinners for the needy. She saw the power in fundraising in 2005, on the day she took off her hard hat and walked through the newly built de Young Museum. It was a 10-year effort in which she had raised $208 million from 7,014 private donors after voters defeated two bond measures to restore the earthquake-damaged original.

What she brings to fundraising that a man wouldn’t, she says, is no fear of rejection. “I think men are very sensitive, and they don’t want to take a chance if they think they’ll be rejected,” Wilsey says. “If someone says no, I just go to the next person. I say, ‘I’m not raising money for myself to pay my Saks [Fifth Avenue] bill. It’s for a building.’ You can be successful for the cause if you have a passion. And if you have a passion for something, you don’t take rejection personally. You just work harder to make it happen.”

Photos by Drew Altizer Photography