Oenophiles in the US have been discovering Georgian wines as if the country had just begun making it, although Georgia is the historically accurate birthplace of wine. The United States and the rest of the world are simply discovering its renaissance.

Georgia, considered the French Riviera of Russia, is sited between the Caucasus Mountains and the Black Sea. About the size of Connecticut, more than 500 types of grapes are unique to this country. How? Because of its biodiversity. In one day, a drive across the country brings you through rainforests, deserts, grasslands, glaciers, and glacial valleys.

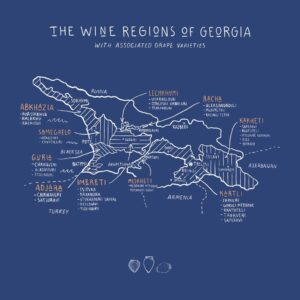

To the cooler west of the country, where the wine regions have such exotic-sounding names as Imereti, Guria, Samegrelo, Racha, Lechkhumi, and Adjara, the soil structure is heavy in clays and volcanic materials, attributable to low pH levels. To the east, the climate grows warmer and drier and the soil tends to be higher in pH, with limestone and sand.

The fact that Georgia is one of the oldest winemaking regions in the world came to light five years ago when archeologists discovered qvevri (pronounced “kway-vree”), traditional clay vessels used in winemaking. Inside the qvevri were grape seeds dating to 6,000 BCE. Today, winemakers in Europe and America are using concrete “eggs” similar to qvevri for storing and aging wine.

UNESCO was so amazed by the longevity of these ancient clay jars that they included qvevri on its Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2013.

Georgia’s exotic grape varietals include Saperavi, Mtsvane Kakhuri, Rkatsiteli, and Chinuri, to name a few, but it’s the small percentage of wines created in qvevris that have caught the attention of U.S. oenophiles. These large, egg-shaped, beeswax-lined, porous terracotta vessels are first filled with grapes, skins, and stems for a few weeks, and then covered and buried underground for six months.

Sommelier Taylor Parsons moderated a recent, virtual Wines of Georgia tasting organized by Marq Wine Group. He introduced a variety of qvevri wines from various producers.

“It’s a huge spectrum of production,” said Marq’s Trade Director, Julie Peterson. “Everyone has one in their marani (cellar)” she says of the ongoing qvevri tradition.

The challenge, however, is keeping these artisanal vessels spotlessly clean. Iago Bitarishvili, co-host with Taylor during the virtual tasting, is one of Georgia’s most prominent winemakers who scrubs his qvevris for two weeks in between uses.

One qvevri can hold 1,500 liters of wine, but it does not impart any flavor profiles to the wine like oak barrels do. The vessel is intended to be neutral.

Due to its bulbous shape and pointed bottom, the vessel performs differently from round, flat-bottomed barrels, and, in fact, act as a natural filtration system, enhancing the natural essence of Georgian wines.

During the virtual tasting, Taylor offered a brief background on Georgia’s political and winemaking history. Beginning in 1200 BC, Georgia endured an almost continuous series of invasions across every one of its borders. The Russian Empire assimilated it in 1801 (throughout the 19th century, Georgia winemakers made wines that were heavily influenced by European styles) and the Soviet Union absorbed it in 1922, when all vineyards became nationalized. The Soviet conquest was almost, but not quite, the death knell for winemaking in Georgia.

A wave of the deadly grape fungus, phylloxera and controlling programs initiated by (native Georgian) Joseph Stalin and perpetuated by Nikita Kruschev continued to assault the industry. When the Soviet Union fell in the 1990s, state properties, including vineyards, again became private. Then came 15 years of civil unrest, known by countrymen as the Dark Time.

In 2006, Georgia’s wine industry resumed development. Grapes are a major agricultural product, and wines now being made in a drier, western style generate good revenue. Alas, a full 90 percent of Georgia’s export market was under embargo, a condition that remained in place until 2013.

In the past seven years, families who once made wine for their own personal consumption have expanded and transitioned into the commercial sector. Their political views are sometimes posted as signage outside their wineries, delineating who is welcome and who is not.

“All are welcome who agree the Russian government occupies 20% of the land.”

Under Vladimir Putin, Georgian winemaking is still threatened, as Russia continues to occupy two regions of Georgia and its fertile, grape-growing lands. In the meantime, the wines of Georgia are enjoying new audiences in Europe and in the United States, where interest in international wines is trending.

Shortly after artisanal winemakers like Iago Bitarishvili were able to commercialize, Georgia launched a New Wine Fair in 2010. Attendance at the fair was encouraging; and, within 12 months, Iago’s wines were being distributed in the United States.

In Georgia’s central winemaking region, Iago has made a reputation as a key producer of Chinuri, an unfiltered wine made with white grapes that undergo a skin-on maceration for six months. The wine is racked in spring, bottled in early fall, and marketed in America as orange wine.

Kakheti, in the east, is Georgia’s most popular winemaking region. Grapes grown there produce less acidic wines that pair well with the rich food and cheeses of this primarily livestock-herding area. Varietals from this region include Saperavi, Rkatsiteli, Mtsvane Kakhuri, Kisi, and Khikhvi.

Sommelier Taylor says, “In Kakheti, wines tend to exhibit a very strong flavor, are usually higher alcohol and more robust, and have longer skin macerations by many months; these are burly wines.”

My personal favorite from the virtual tasting was a 2018 Artanuli Saperavi from Kakheti, made by winemaker Kahka Bershvili. Similar to a Piedmont style Nebbiolo, these biodynamic Saperavi grapes spent nine months in qvevri, yet the cost here in the US is less than $30 a bottle.

On a separate occasion, I tasted a few wines made in the western style, sans qvevri. The grapes were harvested from the district of Telavi, in the village of Tsinandali. A glass of Sun Wine 2018 Tsinandali ($16) made from Rkatsiteli and Mtsvane grapes produced a pale, white dry wine with notes of anise.

Another Sun Wine I enjoyed is imported by Sada Wine of Philadelphia. The 2018 Saperavi (translation: “to give color”) was made with 100 percent Saperavi grapes. An immediate smoky, cherry bouquet led to a fabulous pomegranate flavor in this medium-bodied dry red wine worthy of far more than its US cost of $17. Paired with grilled steak or lamb, you can’t go wrong.

Wine made with grapes from the west of Georgia offer more iron richness in its soils, said Taylor, who continued, “Imereti, a mountainous, densely forested area of Georgia is the most significant part of the west, with only 15 percent of planted hectares, but they’re making some incredibly compelling wines.”

As you head east, the wines become even more forest-y, said Taylor. “Interestingly, the wines here tend to have higher acidity. They’re a little bit fresher, and stylistically, they use less skin maceration in the east, and their cuisine matches that.”

Food is an integral element of wine tasting experiences in Georgia. Every. Single. Day.

The Supra (Persian translation: “tablecloth”) is a tradition of Georgian hospitality that’s become a favorite attraction for the tourists who are slowly filtering into the area. It’s a feast that occurs three times a day, welcoming guests with an abundance of food and drink—and singing.

Supras are led by a tamada, or toastmaster, who introduces multiple toasts and tales throughout the wine-centric feast. Tamadas are required to consume large amounts of alcohol without becoming drunk: the toast he gives, and the subsequent stories relayed, are too complex for tipsiness.

Whatever the topic, guests at a supra raise their glasses, but no one drinks until the tamada has spoken. Then, toasts circle the table counter-clockwise before the next speaker raises his or her glass and drinks until it’s emptied.

Traditional Georgian toast subjects can range from God and the Virgin Mary to saints, ancestors, and friends. There’s even a toast for a supra following a burial.

An excellent way to get the feel of Georgia and to absorb the unique concept of the supra—and perhaps plan your own—is to watch the documentary, Our Blood is Wine on Amazon Prime.